Lesson 19: Chicken Feet Bring Equity Into Our Food Access System

About This Blog:

In this writeup, you’ll see how personal bias, social inequities, and racism undermine health and create challenges to achieving equity across our food system at an individual, organizational, community, and societal level. Emma Witwer, food security expert and registered dietitian, brings these concepts to life by share stories of her own bias, limitations, and growth while feeding her community.

About the Author:

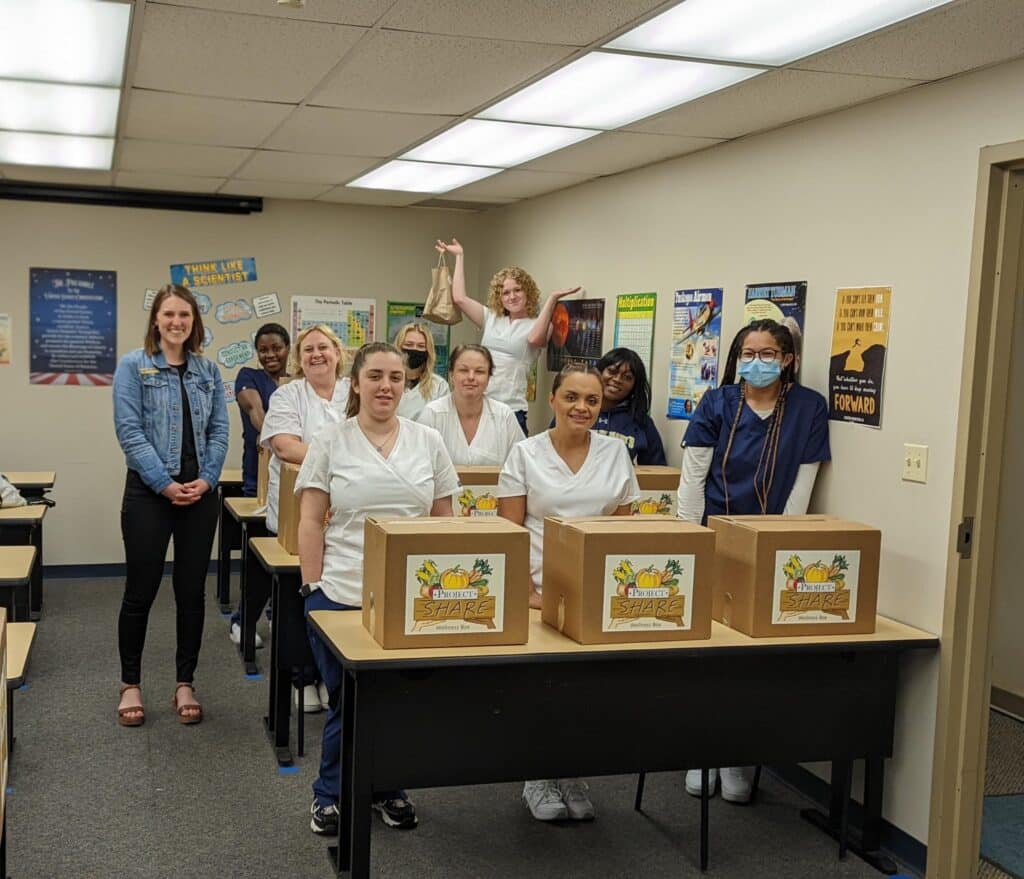

Emma Witwer, RDN, LDN is a Registered Dietitian and the Nutrition Coordinator at Project SHARE, a large food pantry in Central Pennsylvania and former intern at Food Dignity. Project SHARE’s organizational mission is to reduce food insecurity for neighbors in the greater Carlisle area by offering access to nutritious food, programs, and a support network that promotes self-sufficiency, fosters dignity, and instills hope.

Three banana boxes were sitting in the freezer, filled to the brim with 1 lb. packages of chicken feet. Every time I walked into the freezer to re-stock the pantry shelves, I bypassed them and grabbed what I thought were the more desirable protein options—chicken breast, ground turkey, beef. I even went so far as to move the chicken feet to the back corner of the storage freezer. It was beyond my frame of reference to think that any of Project SHARE’s food pantry clients would want chicken feet, so why take up the shelf space adding them to the pantry?

Later that week, a volunteer who was stocking shelves discovered the chicken feet and added an entire box to the pantry. Within 30 minutes, the chicken feet were gone. He re-stocked the pantry with another box. Again, the chicken feet flew off the shelves. In just three hours, the three banana boxes of chicken feet were gone. The food pantry clients of Asian descent were thrilled to have chicken feet as a protein option that day.

That day I became aware of one of my biases. The foods that I, as a young, white, registered dietitian, found desirable are not universally desirable foods. Every race, culture, religion and social class have unique food preferences, and this variety of wants and needs is important to actualize in the food access system.

Yet I am not the only one who has had a white washed perspective. The food system and the charitable food network in the United States skews toward white privilege. In an interview with Clancy, Anjali Prasertong, a dietitian advocating for a more equitable nutrition and food system, highlights that non-profit leadership is predominantly white and do not have the lived experience of poverty or food insecurity. Furthermore, the New York Times wrote an expose article in 2020 about the lack of diversity and inclusion within the dietetics profession.1 For a profession lauded as the health authorities of the country, nutrition recommends bias toward whiteness. Within the food access and nutrition space, there is a lack of diversity, which inhibits health equity.

In a conversation with Clancy, Dr. Kate of the Burt Research Lab at Lehman College, who studies institutional and systemic racism within the dietetics profession shares that there is no one idealized diet and that we need to embrace that people eat different foods, and there are different patterns of healthy eating. She continues, in order to create change, the food access system needs to ask communities what they want. We cannot make assumptions about what foods people want and need.

As I became aware of my bias, I began to reflect on the other food pantry programs I coordinate, and I began to reflect on the Summer Feeding 4 Kids program. When school is out of session, Project SHARE provides free breakfast and lunches to children in the community. In the spirit of centering client and community voices, I launched a survey and hosted focus groups. Two major themes emerged. One— families wanted a non-dairy milk option. Two— families wanted the option to receive vegetarian meals. When these changes were implemented in the summer of 2023, diversity of the program increased. The program was now better serving the dietary needs of a racially and ethnically diverse population. Lactose intolerance is widely prevalent in non-white communities, with up to 80% of Black Americans and 90% of South Asians having lactose intolerance.2 For the families requesting vegetarian meals, the primary reason was religious. For families observing halal eating practices or abstaining from pork requesting vegetarian meals ensured they would receive foods that honored their religious observances. As the program winds down for the summer, about 600 children have been served weekly with over 80,000 meals served. Because of these two menu changes, a more diverse population has been served through this program than in summers past. By listening to the community and offering choice, the program made a few small steps forward in generating a more equitable solution to summer hunger.

To create a more equitable food system and cultivate more food dignity in the food access space, we must center client voices, act on feedback and create a culture of choice, so that individuals and families are given the dignity of choosing what is best for them.

More on Summer Feeding 4 Kids Program can be found here. Find more on all that Project SHARE does for the community at their website.

Sources:

- Is American Dietetics a White Bread World? These Dietitians Think So, an article found within the NYTimes

- Is School Milk Dietary Racism? by Anjali Prasertong

Leave a Comment

Welcome to the Food Dignity® blog, where each article exposes the truth about hidden hunger and food insecurity.

Want to learn more about how we might work together?

Fight hidden hunger by becoming a

Food Dignity® Champion and take the HIDDEN HUNGER PLEDGE >